Le paludisme tue beaucoup. Mais moins qu’ils ne disent

Pour une raison que j’ignore dans de nombreux extraits cités précédemment,

le nombre de morts imputable au paludisme est majoré. Il est fait état de 1

ou 2 voire 3 millions de morts par an. C’est une maladie qui tue beaucoup

mais sans atteindre ces niveaux-là. Du moins plus maintenant.

En 2006 le nombre de décès était estimé entre 610 000 et 1 212 000 par l’OMS. En 2010 c’était entre 490 000 et 836 000 morts par an, toujours

selon l’OMS. Et en 2012 entre 473 000 et 789 000. Pour retrouver des

nombres approchant les 3 millions de morts il faut remonter aux années 1990.

En 1994 il y avait de 1.5 à 2.7 millions de morts à cause du paludisme.

Et en fait le nombre de morts dû au paludisme n’a cessé de décroître depuis

l’après-guerre. Partout ? Non. L’Afrique sub-saharienne fait figure

d’exception. Mais toutes les autres zones géographiques présentent un taux de mortalité en baisse.

Si on suit l’explication des personnes citées précédemment on a du mal à

comprendre la raison de ces différences d’évolution. Soit le DDT a été

totalement interdit malgré son efficacité contre le paludisme et alors le

nombre de morts aurait dû également augmenter en Amérique latine ou en

Asie, ou alors le DDT n’a pas vraiment été interdit partout. Notons aussi que les personnes mourant du paludisme vivent souvent dans des régions très pauvres. Dans ce cas les morts à déplorer peuvent avoir des causes diverses. C’est le cas du paludisme, où pour plus d’un enfant sur deux, la sous-nutrition est une cause sous-jacente du décès. Attention, donc, aux explications trop simplistes.

Si on suit l’explication des personnes citées précédemment on a du mal à

comprendre la raison de ces différences d’évolution. Soit le DDT a été

totalement interdit malgré son efficacité contre le paludisme et alors le

nombre de morts aurait dû également augmenter en Amérique latine ou en

Asie, ou alors le DDT n’a pas vraiment été interdit partout. Notons aussi que les personnes mourant du paludisme vivent souvent dans des régions très pauvres. Dans ce cas les morts à déplorer peuvent avoir des causes diverses. C’est le cas du paludisme, où pour plus d’un enfant sur deux, la sous-nutrition est une cause sous-jacente du décès. Attention, donc, aux explications trop simplistes.

Attention à l’échelle horizontale qui n’est pas constante ! Légende : trait plein : Afrique sub-Saharienne, trait en pointillés : reste du monde

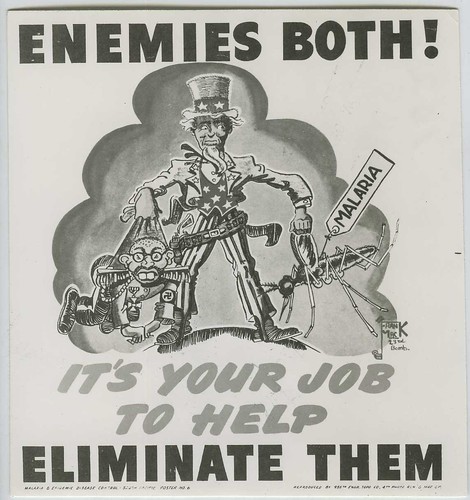

L’interdiction du DDT

Parlons d’abord de l’interdiction du DDT. Le DDT a effectivement été

interdit aux États-Unis en 1972 suite à une décision de l’EPA, l’agence de

l’environnement du pays. Si le cœur vous en dit, vous pouvez aller voir un rapport rédigé trois ans après l’interdiction et qui passe en revue les

nouvelles données venant confirmer ou infirmer ce qui était connu à propos

des risques associés au DDT. Aux États-Unis la principale utilisation du

DDT était à 80% dans l’épandage dans les champs de coton. Le pays n’avait

plus de problème de paludisme.

Le rapport rappelle que quatre autre rapports produits entre 1963 et 1969 ont

recommandé un abandon progressif du DDT dans un intervalle de temps limité

(p.252). Il précise aussi que l’interdiction ne concerne pas les

utilisations pour quarantaine, pour la santé publique ou pour l’exportation

(p.255). Le contraire est pourtant souvent diffusé. L’EPA a également donné

des autorisations ponctuelles à l’utilisation du DDT dans certaines

situations.

Qu’en est-il à l’heure actuelle aux États-Unis d’Amérique ? Il est toujours possible d’y produire du DDT mais il doit être exporté. Il existe toujours

des exceptions à l’utilisation du DDT sur le territoire : pour les urgences

médicales (incluant les maladies comme le paludisme).

Qu’en est-il pour l’OMS ? A-t-elle interdit l’utilisation du DDT ?

Impossible de dire qu’elle ne l’a pas interdit. Mais je n’ai jamais vu le

moindre document de l’OMS annonçant une interdiction du DDT. De toute façon

on voit mal ce qui permettrait à l’organisation l’interdiction d’un

insecticide.

La politique anti-paludisme de l’OMS

C’est évidemment l’OMS (l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé) qui est à

l’origine de la campagne de lutte contre le paludisme.

Avant même la création de l’OMS en 1948, la lutte contre le paludisme apparaît importante et cette maladie figurera parmi la première priorité à la première assemblée de l’organisation. L’OMS se lance rapidement dans

des programmes de contrôle avec de très bons résultats grâce à la

pulvérisation de DDT1.

Encouragé par ces résultats positifs, l’OMS lance une campagne d’éradication en 1955 qui se terminera quinze ans plus tard, en même

temps qu’une campagne de lutte contre le pian2. À cette époque

l’OMS est jeune et n’a pas encore l’expérience de programmes internationaux

de lutte contre une maladie. Les erreurs commises lors de la campagne contre le paludisme serviront pour les campagnes d’éradication qui suivront

(contre la variole, par exemple)3.

L’OMS a mis le paquet contre le paludisme. Un tiers de son budget et 500

personnes sont mobilisées sur le programme4.

En 1966 les résultats sont très bons : environ 1 milliard de personnes, ou

60% de la population originellement présente dans des zones à risque de

paludisme, étaient désormais débarassés du paludisme, ou en tout cas ne

posait plus un problème. Cependant le tableau n’était pas complètement

rose. L’Afrique était maintenant le continent qui avait le plus de cas de

paludisme et de décès : aucun progrès n’avait été fait. De fait lorsque la campagne d’éradication de l’OMS a été lancée, personne ne savait comment traiter l’Afrique tropicale5. Quant au Mexique,

où pourtant une campagne féroce a été menée, 4 millions de personnes

vivaient toujours dans des zones où le moustique résistait au DDT et aux

autres insecticides (hé oui ! Il n’y a pas que le DDT)6.

Si la situation était très encourageante à certains endroits cela ne

reflétait donc pas la réalité sur la totalité du globe. Quelle était la

raison de ces problèmes ? Les écolos anti-DDT ? Pas tout à fait.

Selon les documents, les raisons données ne sont pas toujours les mêmes ou

ne sont pas considérées avec la même importance. Mais il n’y a pas de

grosses différences. On peut donc citer7 :

Avant même la création de l’OMS en 1948, la lutte contre le paludisme apparaît importante et cette maladie figurera parmi la première priorité à la première assemblée de l’organisation. L’OMS se lance rapidement dans

des programmes de contrôle avec de très bons résultats grâce à la

pulvérisation de DDT1.

Encouragé par ces résultats positifs, l’OMS lance une campagne d’éradication en 1955 qui se terminera quinze ans plus tard, en même

temps qu’une campagne de lutte contre le pian2. À cette époque

l’OMS est jeune et n’a pas encore l’expérience de programmes internationaux

de lutte contre une maladie. Les erreurs commises lors de la campagne contre le paludisme serviront pour les campagnes d’éradication qui suivront

(contre la variole, par exemple)3.

L’OMS a mis le paquet contre le paludisme. Un tiers de son budget et 500

personnes sont mobilisées sur le programme4.

En 1966 les résultats sont très bons : environ 1 milliard de personnes, ou

60% de la population originellement présente dans des zones à risque de

paludisme, étaient désormais débarassés du paludisme, ou en tout cas ne

posait plus un problème. Cependant le tableau n’était pas complètement

rose. L’Afrique était maintenant le continent qui avait le plus de cas de

paludisme et de décès : aucun progrès n’avait été fait. De fait lorsque la campagne d’éradication de l’OMS a été lancée, personne ne savait comment traiter l’Afrique tropicale5. Quant au Mexique,

où pourtant une campagne féroce a été menée, 4 millions de personnes

vivaient toujours dans des zones où le moustique résistait au DDT et aux

autres insecticides (hé oui ! Il n’y a pas que le DDT)6.

Si la situation était très encourageante à certains endroits cela ne

reflétait donc pas la réalité sur la totalité du globe. Quelle était la

raison de ces problèmes ? Les écolos anti-DDT ? Pas tout à fait.

Selon les documents, les raisons données ne sont pas toujours les mêmes ou

ne sont pas considérées avec la même importance. Mais il n’y a pas de

grosses différences. On peut donc citer7 :

Avant même la création de l’OMS en 1948, la lutte contre le paludisme apparaît importante et cette maladie figurera parmi la première priorité à la première assemblée de l’organisation. L’OMS se lance rapidement dans

Avant même la création de l’OMS en 1948, la lutte contre le paludisme apparaît importante et cette maladie figurera parmi la première priorité à la première assemblée de l’organisation. L’OMS se lance rapidement dans- les résistances des moustiques aux insecticides, dont le DDT ;

- les résistances du parasite aux médicaments ;

- des services de santé peu développés dans certains pays, incapables d’effectuer une surveillance épidémiologique ou de surveiller les foyers de résurgence ;

- les habitudes humaines (dormir dehors, migration saisonnière…) ;

- le manque de personnes compétentes sur le terrain ;

- l’arrêt de la pulvérisation dès que l’incidence est suffisamment basse, pour éviter le développement de résistance ;

- une baisse de la collaboration de la population ;

- une organisation « top-down » quasi militaire ;

- le coût de la campagne (je rappelle : 1/3 du budget de l’OMS).

Inde et Sri-Lanka

J’ai mentionné l’histoire merveilleuse de l’Inde et du Sri Lanka qui ont

réussi à réduire fortement les décès dus au paludisme dans les années 1960

grâce à l’utilisation de DDT. La chute s’est ensuite inversée dans les

années 1970.

L’Inde est passée de 100 millions de cas de paludisme en 1952 à 50 000 une

décennie plus tard. Au Sri Lanka les cas sont passés de 3 millions à moins

de 25 en une décennie14.

Ce nombre de cas est remonté en flèche dans les années qui ont suivi. Ce

n’est pas en raison de l’arrêt du DDT, mais notamment en raison de

l’apparition de résistances de certains moustiques au DDT et la dieldrine15. Autre élément de cette résurgence : le paludisme était à l’origine une maladie rurale, et le programme indien de contrôle de la maladie se concentrait sur ces zones. Or à cette époque la maladie devient urbaine ce qui conduit à la mise en place d’un programme urbain en 1970–197116.

L’incidence de la maladie a ainsi été multipliée par trois entre 1961 et 1966 en Inde, 6 ans avant l’interdiction du DDT aux USA17. Au début des années 1970, l’incidence augmentait exponentiellement et d’autres approches ont été conduites, qui ont nécessité trois décennies pour être complétées18.

Mettre en cause l’interdiction du DDT dans la remontée de l’incidence du

paludisme en Inde et au Sri-Lanka ne reflète pas la réalité. L’incidence a

bien augmenté avant son interdiction aux USA par l’EPA. Des insectes

résistants ont émergé et il semble que les efforts de la campagne

anti-paludisme aient également diminué19. En outre dans le cadre de la mise en place en Inde d’un programme modifié en 1977 (le MPO : Modified Plan of Operation), le DDT est toujours utilisé20.

L’incidence de la maladie a ainsi été multipliée par trois entre 1961 et 1966 en Inde, 6 ans avant l’interdiction du DDT aux USA17. Au début des années 1970, l’incidence augmentait exponentiellement et d’autres approches ont été conduites, qui ont nécessité trois décennies pour être complétées18.

Mettre en cause l’interdiction du DDT dans la remontée de l’incidence du

paludisme en Inde et au Sri-Lanka ne reflète pas la réalité. L’incidence a

bien augmenté avant son interdiction aux USA par l’EPA. Des insectes

résistants ont émergé et il semble que les efforts de la campagne

anti-paludisme aient également diminué19. En outre dans le cadre de la mise en place en Inde d’un programme modifié en 1977 (le MPO : Modified Plan of Operation), le DDT est toujours utilisé20.

L’incidence de la maladie a ainsi été multipliée par trois entre 1961 et 1966 en Inde, 6 ans avant l’interdiction du DDT aux USA17. Au début des années 1970, l’incidence augmentait exponentiellement et d’autres approches ont été conduites, qui ont nécessité trois décennies pour être complétées18.

L’incidence de la maladie a ainsi été multipliée par trois entre 1961 et 1966 en Inde, 6 ans avant l’interdiction du DDT aux USA17. Au début des années 1970, l’incidence augmentait exponentiellement et d’autres approches ont été conduites, qui ont nécessité trois décennies pour être complétées18.Résistance

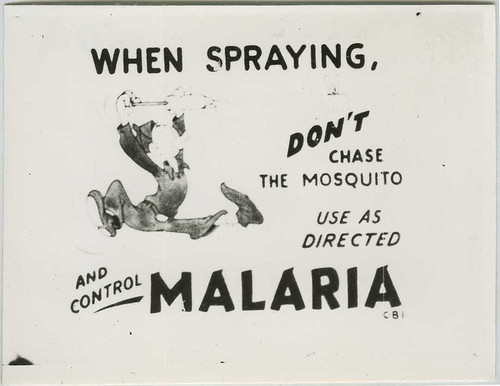

J’ai déjà mentionné le développement de résistance comme une partie de

l’explication. Certains moustiques résistants au DDT ont pu survivre

pendant que leurs congénères non résistants ont été décimés.

Ces résistances (au DDT ou à la dieldrine, autre insecticide) semblent

avoir commencé à émerger à la fin des années 1950, début des années 196021.

La raison de l’émergence de ces moustiques résistants aux insecticides

semble être à la fois l’utilisation en agriculture ou dans la lutte

contre le paludisme22. Dans la partie nord du Cameroun les résistances au DDT ont notamment conduit à arrêter en 1961 un programme de lutte contre le paludisme initié en 195923, d’autres raisons sont également mentionnées (contraintes financières, comportements différents des moustiques, mauvaise mise en place de la campagne, effet résiduel limité du DDT)24.

Un document de l’OMS de 1992 liste les résistances connues à ce jour. De

nombreux pays, en particulier en Afrique sub-saharienne, sont touchés par

des espèces de moustiques ayant une résistance au DDT25. Ce document donne

d’ailleurs au passage une raison du développement des résistances au

DDT : son efficacité. Le DDT se dégrade lentement, ce qui pose des

problèmes en terme environnementaux, mais ce qui est un avantage dans la

lutte contre le paludisme. Or plus il reste longtemps dans

l’environnement et plus il y a des risques que les moustiques résistants survivent au profit de ceux qui ne le sont pas26.

En 2012, des résistances existent toujours en Afrique (Afrique du Sud,

Bénin, Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Côte d’Ivoire, Éthiopie, Ghana, Kenya,

Mozambique, Ouganda, Tanzanie…)27. Une autre étude mentionne l’existence de résistance dès le début des années 2000 au Zimbabwe28. Le lecteur intéressé pourra aussi se reporter à cette étude de 2015 sur l’état des résistances aux différents insecticides dans le monde, selon les espèces de moustiques : les chercheurs notent que la plupart des espèces montrent des résistances et mentionnent la nécessité de développer des moyens alternatifs de lutter contre le paludisme. Désormais des résistances ont été signalées chez plus de 500 espèces de moustiques, dont une cinquantaine qui transmettent le paludisme aux humains29. Cela illustre, si besoin était, de la

continuation de l’utilisation du DDT. Dire que le DDT n’a plus été

utilisé pour lutter contre le paludisme est tout simplement une fable. Il

n’y aurait pas autant de résistance si celui-ci n’était pas utilisé depuis

au moins une décennie.

Des chercheurs ont passé en revue les publications scientifiques analysant les populations de moustiques résistantes aux insecticides. Ils mettent en lumière un accroissement des résistances au DDT et au pyréthroïde dans les pays d’Afrique tropicale entre le début des années 2000 et 2012. À un point tel qu’ils considèrent ces résistances « alarmantes ».

Certains aiment aussi citer le cas de l’Afrique du Sud. En 1996 l’Afrique

du Sud décide de ne plus utiliser le DDT (ce qui signifie donc que le

pays l’utilisait jusque-là) pour passer à d’autres insecticides. En 2000,

le pays fait marche arrière en raison de l’augmentation du nombre de cas

de paludisme. La raison est la réapparition d’une espèce de moustique

A. funestus qui avait disparu avec le DDT mais est réapparu avec les

nouveaux insecticides auxquels elle était résistante30.

N’oublions pas non plus, dans le contexte de la lutte contre le

paludisme, la résistance du parasite aux médicaments31. La lutte contre le paludisme présente deux aspects : la lutte contre

le vecteur (les moustiques) et la lutte contre le parasite (par exemple

Plasmodium Falciparum). Il existe différents insecticides et différents

médicament pour faire reculer le paludisme. Tout focaliser sur le DDT est

une simplification abusive.

Continuation de la lutte

L’utilisation du DDT dans la lutte contre le paludisme semble n’avoir

jamais arrêté dans le monde. J’ai cité préalablement le cas de l’Afrique

du Sud qui n’a arrêté l’utilisation de cet insecticide uniquement entre

1996 et 2000. On pourrait répondre que le cas de l’Afrique du Sud était particulier. C’est exact, il ne s’agit que d’un exemple. Mais il n’est pas isolé. Ainsi que l’illustrent Mabaso et al, le DDT a été utilisé des années 40 jusqu’en 2000 au Swaziland, de 1950 jusqu’en 1997 au Botswana, de 1965 jusqu’en 2000 en Namibie.

Dans un document préalablement cité, faisant l’état des lieux des

résistances, il est question de plusieurs pays continuant à avoir recours

au DDT en 1992. Par exemple le Mexique continuait à l’utiliser : des

résistances existaient sur la côte Pacifique mais pas la côte Atlantique32. Si les voisins directs des États-Unis

continuaient à utiliser le DDT dans la lutte contre le paludisme, cela

illustre bien l’absence de toute pression de leur part. Même chose en

Inde où le DDT était encore utilisé pour protéger 229 millions de

personnes33. Au Zimbabwe, le DDT a été utilisé de 1957 à 1962, de 1974 à 1991 et depuis 2004. En Inde le DDT est utilisé depuis 1977 apparemment sans interruption (ou alors de courte durée)34, avec des résultats très mitigés ce qui laisse penser qu’il ne s’agit pas forcément de la meilleure stratégie35. Difficile de

parler d’interdiction hormis en niant les faits.

Un document de l’OMS de 1979 rappelle que le DDT reste très utilisé aussi

bien en agriculture que pour l’éradication des moustiques et indique que

son remplacement entraînerait une multiplication du coût comprise entre

3,4 et 8,5 fois36.

On peut aussi trouver d’autres documents de l’OMS montrant implicitement

que le DDT continue à être utilisé. Un rapport de 1983 fait état de

l’utilisation du DDT dans la lutte contre le paludisme au Bangladesh et

aux Maldives. Un document de 1985 parle par exemple d’une moustiquaire qui

« tue les moustiques », pour ceux qui ne voudraient plus de DDT à

l’intérieur des maisons. Un rapport de 1997, s’intéresse au test de

nouveaux insecticides pour remplacer ceux « normalement utilisés » : le

DDT et le malathion. Un document de 1998 rappelle la position de l’OMS :

elle approuve l’utilisation du DDT par pulvérisation dans les maisons,

contre les vecteurs du paludisme ou de la leishmania. Elle dit aussi qu’en

cas du banissement du DDT37 des méthodes alternatives efficaces et

abordables doivent être disponibles en amont38. Un rapport de 2004 cite d’autres rapports (le

plus ancien datant de 2000) et réaffirme sa recommandation d’utilisation

du DDT à condition qu’il soit restreint à l’utilisation en pulvérisation

intérieure, qu’il soit efficace, que les précautions de sureté soient

prises39. Dans ce

contexte, un communiqué de presse (et non un rapport) de l’organisation en

2006 semble contradictoire. Il indique que l’organisation a soutenu

l’utilisation du DDT en pulvérisation interne jusqu’au début des années

1980 mais a ensuite arrêté en raison des questions sur l’environnement et

la santé. Or aucun des rapports consultés ne mentionne ces préoccupations. Au contraire des rapports du début des années 2000 continuent à recommander l’utilisation du DDT. Ce communiqué a-t-il été intoxiqué par la propagande servie par

certains, cherchant à faire croire que l’utilisation du DDT pour la lutte

contre le paludisme aurait été bannie à travers le monde ?

Le rôle de l’USAID

Il est parfois dit que USAID, l’agence des États-Unis pour le développement international, a coupé les financements aux campagnes d’éradication du

paludisme ayant recours au DDT. Il est exact que l’USAID a diminué les

financements. En revanche, rien n’indique que ce soit à cause du recours au

DDT. Il semble au contraire que la raison soit l’échec de la campagne

d’éradication de l’OMS avec le changement de stratégie de l’OMS qui a suivi. Cela a conduit à une baisse globale des financements de l’USAID ainsi que de l’UNICEF (la crise pétrolière de 1970 n’y est pas non plus étrangère)40.

Diminution des financements ne signifie pas pour autant arrêt des financements. L’USAID a financé des programmes dans la lutte contre le paludisme utilisant du DDT notamment au Zaïre (1976–1981)41, à Haïti42, ou encore au Népal43. Il existe probablement d’autres cas, mais les documents consultables publiquement ne spécifient pas forcément quels insecticides sont utilisés dans la lutte contre le paludisme. Impossible, dans ces conditions, de dire si l’USAID a soutenu des programmes anti-paludisme utilisant du DDT ou un autre insecticide.

Santé et environnement

Quels sont les risques du DDT sur l’environnement et sur la santé humaine ?

La notice du NPIC (centre d’information étatsunien sur les pesticides) sur

le DDT précise qu’il n’y a pas de lien trouvé chez l’humain entre cancer

du sein et DDT. Même chose pour des ouvriers ayant travaillé dans une

usine produisant du DDT. En revanche, la notice parle d’un impact

important du pesticide sur les animaux aquatiques. Précisons également

que cette notice date de 1999. La recherche a probablement évolué sur le

sujet.

Des informations plus récentes, justement, il en existe. Un article de l’agence européenne de l’environnement faisait en 2013 un état des lieux des

connaissances sur le sujet.

Il semble que l’exposition avant 14 ans au DDT soit une cause de cancer du

sein44. La pulvérisation de DDT dans les maisons est également associée

à des défauts urogénitaux externes chez les nouveaux-nés. Mais le rapport

appelle à plus de recherche pour établir de possibles prédispositions

génétiques ou épigénétiques45. L’exposition au DDT avant la

naissance est liée à des retards neuro-développementaux durant l’enfance46

Une expertise collective de l’Inserm sur les pesticides signale une

augmentation du risque de myélome multiple chez les agriculteurs ayant été

exposés au DDT47. L’expertise indique qu’il n’y a pas de lien

convaincant entre exposition aux organochlorés (sans préciser lesquels) et

malformations génitales chez le garçon mais identifie de fortes présomptions

d’un impact sur la croissance et le développement de l’obésité chez l’enfant48.

Elle

mentionne aussi la dégradation de paramètres spermatiques ou un allongement du délai

nécessaire pour concevoir, chez les personnes les plus touchées par le

DDT49, ou encore la perturbation

de l’immunité50.

Enfin une récente étude ayant procédé au suivi de 9300 femmes pendant 54 ans montre que l’exposition in utero au DDT est un prédicteur du développement de cancer du sein à l’âge adulte (presque 4 fois plus de risque). L’étude stipule que ni l’âge des mères, leur taux de graisse, leur poids, leur origine ethnique ni leurs antécédents de cancer du sein ne parviennent à expliquer cela.

Prolonger

Maintenant qu’il est bien établi que les écologistes ne sont pas responsables de millions de morts à cause du DDT, vous pourriez être intéressés de savoir comment cette fable est apparue. Pour cela, direction l’article suivant.Mises à jour

- 01/06/2018 : Ajout d’un article sur l’évolution des résistances des moustiques au Cameroun : Antonio-Nkondjio et al, 2017

- 05/05/2018 : Mise à jour de nombreux liens brisés

- 19/09/2016 : Ajout de l’article de Sharma, 2003 qui évoque l’historique de l’utilisation du DDT en Inde

- 08/04/2016 : Ajout de deux articles de synthèse : Mabaso et al, 2004 ainsi que Soko et al, 2015. Ces deux articles mentionnent l’utilisation du DDT dans les années 80 et 90 dans divers pays d’Afrique. Ils parlent aussi de résistance au Zimbabwe.

- 25/12/2015 : Ajout d’une étude sur l’étendue des résistances dans différents endroits dans le monde.

- 28/09/2015 : Reformulation suite à la remarque de Sombrenard.

- 09/09/2015 : Ajout d’une étude sur le lien entre exposition in utero au DDT et cancer du sein.

- 11/06/2014 :

- Ajout d’une référence à un article étudiant l’étendue des résistances en Afrique tropicale. L’article considère que les résistances au DDT et au pyréthroïde augmentent et deviennent très répandues.

- Très intéressant article sur les leçons à tirer de l’échec de la campagne d’éradication. L’article ne mentionne jamais de pressions des ONG qui auraient eu des conséquences néfastes. Il mentionne au contraire l’organisation très top-down, des questions de budget, l’émergence de résistances…

- Précisions ajoutées à propos du paradoxe que représente le communiqué de presse de l’OMS de 2006.

- 3/05/2014 : Ajout des statistiques sur le lien entre sous-nutrition et les décès d’enfants dus au paludisme.

- 26/04/2014 : Ajout des programmes anti-paludiques financés par l’USAID et ayant recours au DDT.

- 26/04/2014 : Ajout d’une nouvelle référence au développement de résistance au Sri-Lanka.

- « By 1951, WHO teams were involved in 22 malaria control projects, mainly in Asia. While WHO provided the professional staff, UNICEF supplied transport, equipment, insecticides, and drugs— a pattern that was rapidly becoming the norm for the mass-campaign approach to international public health in the 1950s and 60s. The initial results were extremely encouraging. By 1955, the number of malaria cases worldwide had dropped by at least a third. Over half the world’s population then estimated to live in malarious areas was protected from the disease by DDT spraying. » (p. 8–9) [↩]

- Ce qui nous amène en 1970 soit une époque à peu près contemporaine de l’interdiction du DDT aux États-Unis. Mais la lutte contre le pian n’a pas du tout recours au DDT. Il s’agit uniquement d’une coïncidence : « As a reminder, the yaws and malaria campaigns began more or less at the same time, about 1955, and were effectively terminated some 15 years later, in 1970 or soon thereafter. The launch of each was triggered by the introduction of a new technology — an injectable single-dose long-acting penicillin — for the treatment of yaws and the availability of large quantities of the inexpensive insecticide DDT for use in the malaria programme. » [↩]

- « The programme failed, but lessons derived from malaria eradication were central in shaping the smallpox eradication strategy » [↩]

- « Of the two programmes, malaria was, by far, the most important and during its 15 years of existence, it accounted for more than one-third of WHO’s total expenditures and its 500-person WHO staff dwarfed all other programmes [↩]

- « This overoptimistic environment prevented the recognition of general problems in the conception of the campaign, which was based on an exaggerated extrapolation of early local experiences that, although successful, represented a very limited variety of epidemiological situations. Actually, it was obvious from the start that nobody knew how to deal with the problems of tropical Africa; this was one of the main objections to the GMEP in the 1955 WHA. » Some lessons for the future from the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955-1969). [↩]

- « WHO’S Expert Committee on Malaria, meeting in September 1966, noted with satisfaction that nearly 1000 million people, or 60% of the population of the originally malarious areas of the world, were living in areas where malaria had been eradicated or was no longer a major health problem. But despite the undoubted gains, the problems were also legion. In Africa, which had more malaria cases and deaths than any other continent, no progress had been made at all. And even in Mexico, where a massive, military—style campaign had been waged with great tenacity, over 4 million people lived in areas where the anopheles mosquito still held out against DDT and other insecticides » (p. 9—10) [↩]

- « There were good reasons for these problems, few of which had been foreseen a decade earlier. First, there was the extraordinary capacity of both the anopheles mosquito and the malaria parasite to develop resistance to insecticides and drugs. There was also the problem of inadequate case detection combined with poorly developed health services, which were unable to cope with epidemiological surveillance and sporadic outbreaks of the disease. Then there was the scarcity of experienced field workers. Finally, there was the most important factor—cost. In country after country, the cost of antimalaria activities was accounting for a third or more of the health budget—a burden that could no longer be sustained. Moreover, the major international donors—first UNICEF and later USAID -felt obliged to scale down their support and finally withdraw it. » p.10 « Undoubtedly, technical difficulties related to resistance of plasmodia or anopheles to drugs or insecticides are only partly responsible for the present fiasco. The other actors are: inadequate case detection; premature move into the consolidation phase (since the health services were inadequate to deal with the sporadic outbreaks and continued transmission of malaria); shortage of experienced professional and field personnel; and last, but far from least, the rising cost of antimalaria activities and the inability, if not unwillingness, of many governments to make the requisite resources available for the control of a disease that was, or was supposed to be, close to eradication » p.16 « The situation was greatly confused because in some areas sloppy work, leaving many houses without proper spraying, allowed the disease to persist without showing signs of eradication. Many malariologists believed that more efficient spraying was all that was needed anywhere to achieve their goal. The experience of the last 20 years has shown clearly that they were wrong. Another unfavourable factor was introduced by the Expert Committee on Malaria. It advised the withdrawal of spraying as soon as the incidence dropped below one case in 10 000 population, in order to employ the insecticide for as short a time as possible and thus avoid the development of resistance in the vectors. The experience of many countries, the saddest being Sri Lanka, has clearly indicated that in the presence of powerful vectors, this strategy was wrong. » p.18 « The programme failed, but lessons derived from malaria eradication were central in shaping the smallpox eradication strategy. Three operating principles were of particular importance. First was the relationship of the programme itself to the health services. It was a tenet of the malaria eradication directorate that the programme could not be successful unless it had full support from thc highest level of government. This translated into a demand that the director ol the programme in each country report directly to the head of government and that the malaria service function as an independent, autonomous entity with its owm personnel and its own pay scales. Involvement of the comrmunity at large or of persons at the community level was not part of the overall strategy. Second, all malaria programmes were obliged to adhere rigidly to a highly detailed, standard manual of operations. It mandated, for example, identical job descriptions in every country and even prescribed specific charts to be displayed on each office wall at each administrative level. The programme was conceived and executed as a militarv operation to be conducted in an identical manner whatever the battlefield. Third, the premise of the programme was that the needed technology was available and that success depended solely on meticulous attention to adnministrative detail in implcmenting the effort. Accordingly, research was considered unnecessary and was eftectively suspended from the launch of the programme. » p.2 « However, in spite of this powerfully delivered effort, the anticipated goal, the eradication of malaria, was not achieved in any country of the region. The prohibitive economic and political costs of operating the malaria control campaigns, which from 1954 onward became formally instated by the World Health Organization as Malaria Eradication Campaigns (48), were not sustainable. This, combined with emerging resistance of the parasites and their vectors to the chemicals used to attack them, led, from the early 1970s, to resurgence of malaria transmission throughout southern Asia and the Western Pacific. Most damaging was the emergence of multidrug-resistant P. falciparum, including total resistance to chloroquine. Since the mid-1960s, chloroquine resistance has spread inexorably outward across the tropics of Asia and the Western Pacific and into Africa from a focus of origin in Southeast Asia » Evolutionary and Historical Aspects of the Burden of Malaria « Before the Second World War, most of western Europe had virtually eliminated the disease by focal vector control and by making diagnosis and treatment widely available. In the decade that followed, the availability of DDT and chloroquine, both with impressive efficacy, led to a resurgence of campaign spirit and, in 1955, the launching of the Global Programme for Malaria Eradication, a campaign that targeted all endemic countries except mainland sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. The cam- paign demanded perfect execution of prescribed activities by a highly dis- ciplined workforce, which was to spare no effort in reaching the remotest houses. Nevertheless, mosquito vectors and parasites did not respond everywhere as expected, and progressive attrition began in both the operational esprit de corps and discipline as well as in the collaboration of the population. The progress of the campaign slowed, and malaria outbreaks occurred during the consolidation phase of the programme in some areas that had initially responded well. Analysing the failures during the consolidation phase, WHO recognized that the basic requirements for achieving and sus- taining malaria control are (1) integration of malaria control into a reason- ably well-established health system, (2) an uninterrupted, continued effort and (3) research into new and improved tools. […] [En Inde] In the late 1960s, social, financial, administrative and operational problems began, including communities refusing DDT spraying, shortage of supplies, financial constraints, hilly terrain and inaccessible areas, administrative problems, inadequate surveillance, shortage of experienced, trained personnel and understaffing at all levels. As a result, the initial gains could not be maintained. » Global malaria control and elimination : report of a technical review, 2008. « As mentioned above, antimalarial interventions other than indoor residual spraying were abandoned. Even the use of antimalarial drugs as a complementary measure was considered redundant at the beginning. At the same time, there was a general disregard for social and cultural barriers, which often prevented the acceptance of the campaign activities in many of the “remote areas.” […] As a result, a new “pre-eradication programme” was established, mainly for Africa, with the aim of developing the required health infrastructure in parallel with the preparatory phase of the campaign. Unfortunately, there were no models of the minimum infrastructure required and the development of the “basic health services” continued to respond mainly to financial and political motivations. […] A public health service is needed to support malaria surveillance, even though there are still major disagreements among experts about when or how antimalarial programmes should be integrated with the health services. […] As highlighted by the Primary Health Care movement, active participation of communities in the understanding of and actions for the solution of their health problems needs to be incorporated into antimalarial programmes. » Some lessons for the future from the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955-1969). [↩]

- « global eradication, though theoretically possible, will continue to be beyond reach for many years to come » (p.19) [↩]

- « WHO appointed special teams of economists, public health

administrators, malariologists, and statisticians to study malaria

eradication programmes in nine countries representative of various

situations found in malaria eradication campaigns throughout the world. The

findings of these teams were presented in a report by the

Director-General (;) to the Twenty-second World Health Assembly. The

conclusions and recommendations of the report can be summarized as

follows:

- The planning and budgeting of malaria eradication programmes were not included in or coordinated with the overall national economic development planning. Consequently many eradication programmes had been handicapped by lack of sustained government support

- Many countries had embarked on eradication programmes without realizing extent of the commitment involved

- Technical factors including exophilic habits (outside biting and sheltering) of vectors, insecticide resistance, and factors of human ecology (e.g., seasonal migration, habit of sleeping outdoors) though affecting only about 1 % of the areas with eradication pro- grammes, had an adverse operational and psychological impact quite out of proportion to their size

- Serious operational deficiencies were almost invariably encountered. The report stated that « the present methods of eradication, although simpler than those available before… are still laborious and often too expensive for the limited resources of developing countries; unless the present methodology is further simplified, global eradication, though theoretically possible, will continue to be beyond reach for many years to come ». This was an important statement, but it was not given much emphasis in the report

- « During the transition period of the IMCP (1965-68), the DDT consumption declined gradually from 3,626 tons in 1964 to 0.7 ton 1968 while the SPR increased 11 times, from 0.04% in 1965 to 0.44% in 1968. As the IMCP was better organized, the annual use of DDT increased steadily from 45 tons in 1969 to 1,390 tons in 1978, an increase of 31 times. The increase in the number of houses sprayed and population covered was about 35 times during the same period. DDT consumption appeared to be relatively constant during the period in terms of houses sprayed (0.74-1. 0 kg/house) and population protected (0.15 – 0.20 kg/capita) throughout the province. However, the number of houses sprayed or population protected varied with regencies. In Banjarnegara, where the DDT consumption has been highest among the 29 regencies, the overall use of DDT was 808 g/house and 162 g/inhabitant. » (p.2) [↩]

- « Although the Global Malaria Eradication Campaign did not achieve its ultimate objective, it was credited with eliminating the risk of disease for about 700 million persons, mainly in North America, Europe, the former Soviet Union, all Caribbean islands except Hispaniola, and Taiwan. High socioeconomic status, well-organized healthcare systems, and relatively less intensive or seasonal malaria transmission were the main factors in attaining the disease elimination goal in these regions. Malaria was effectively suppressed in subtropical and tropical areas of Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Notable among those efforts was the near eradication of malaria in India, where the annual number of malaria cases was reduced from an estimated 75 million to about 100,000 in the early 1960s. These reductions were not sustained after the eradication period because limited resources were devoted to malaria control. Because of the perceived intractability of the disease and concerns about infrastructure and sustainability, large swaths of Africa were left out of the global eradication efforts » Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) for Indoor Residual Spraying in Africa: How Can It Be Used for Malaria Control? [↩]

- « The US/AID became disenchanted with the eradication programme, particularly after the Communicable Diseases Center, Atlanta, took over the technical direction and thrust into the programme young health scientists who were exposed for the first time to the field realities of ealth programming in countries of the Third World and who did not have the mental humility to learn before they made their criticisms of the malaria services of WHO, US/AID, and the governments. This resulted in decentralizing the malaria assistance and placing its control in the hands of the local directors of the US/AID missions, who were more interested in developing unipurpose family-planning programmes, which received high priority in their policies. As a result, the malaria eradication services began to lose seasoned field malariologists and paramed- ical workers who were attracted to the family-planning programmes by the monetary incentives offered. The global smallpox campaign also took full advantage of the facilities existing in the national malaria eradication services and was a factor in accelerating their dismantling » (p.9) [↩]

- « In 1988, DDT was replaced by deltamethrin and lambda-cyhalothrin due to the international lobby against persistent organic pollutants (Freeman 1995). » Mabaso et al, 2004 [↩]

- « Indian authorities instituted a programme of medical treatment and pesticide application in 1952 which within a single decade reduced the number of cases from over 100 million to 50,000. Ten years later, using the same methods, health workers in Sri Lanka cut the annual incidence of malaria from three million cases to fewer than 25. » [↩]

- « Instead of dwindling to insignificance, the number of infected individuals rose again to distressing proportions. In India, which had served as a showplace for WHO policies, five million people were soon infected; in Sri Lanka, two million people became sick again almost overnight; and in Central America infection rates grew to previously unknown levels. Moreover, unlike earlier outbreaks, this new plague was often carried by mosquitoes which had become resistant to pesticides like DDT and dieldrin and could not be controlled by conventional means » http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v293/n5829/abs/293181a0.html « However, in spite of this powerfully delivered effort, the anticipated goal, the eradication of malaria, was not achieved in any country of the region. The prohibitive economic and political costs of operating the malaria control campaigns, which from 1954 onward became formally instated by the World Health Organization as Malaria Eradication Campaigns (48), were not sustainable. This, combined with emerging resistance of the parasites and their vectors to the chemicals used to attack them, led, from the early 1970s, to resurgence of malaria transmission throughout southern Asia and the Western Pacific. Most damaging was the emergence of multidrug-resistant P. falciparum, including total resistance to chloroquine. Since the mid-1960s, chloroquine resistance has spread inexorably outward across the tropics of Asia and the Western Pacific and into Africa from a focus of origin in Southeast Asia » Evolutionary and Historical Aspects of the Burden of Malaria « [En Inde] Slowly but steadily, rural mosquito populations (A. culicifacies) evolved to withstand or avoid the killing effect of DDT. That was the beginning of the decline of DDT. As resistance spread, a dramatic resurgence of malaria occurred in the second half of the 1960s and in the 1970s. » (DDT: The fallen angel, p. 2) « In Sri Lanka, resistance in A. Culicifacies in 1967 was a major factor in the failure to control malaria » (p. 23) [↩]

- « Malaria in India basically had been a rural disease, and therefore NMEP was a rural malaria control programme. During the resurgence of the disease during the late 1960s onwards, malaria cases were multiplying in the urban areas, and the disease was seen diffusing from urban to rural areas that were in the maintenance phase. To address the emerging urban malaria problem, in 1970–71 NMEP implemented the Urban Malaria Scheme (UMS). » (DDT: The fallen angel, p. 2) « Malaria in urban areas was considered to be a marginal problem restricted to mega cities only and not included as part of the National Malaria Eradication Programme in 1958. By the 1970s, incidence of rural malaria dropped drastically to 0·1–0·15 million cases per year, but urban areas reported a rising trend. Around 10–12% of total malaria cases in India were in urban areas at that time » (Malaria elimination in India and regional implications, 2016) [↩]

- « Between 1961 and 1966, disease rates in India increased threefold; by 1970, half a million people caught malaria each year — many in areas where health authorities had recently scored impressive victories. Much the same course of events took place in Sri Lanka, which in 1968 experienced an epidemic that left 1.5 million people stricken. […] In El Salvador, Nicaragua andHonduras […] the incidence of disease in 1975 was three times greater than a decade earlier, before the programmed had started » [↩]

- « By the early 1970s, the malaria incidence (measured as the annual parasite incidence) was seen to be multiplying exponentially nationwide. Other approaches were tried. The ‘urban malaria scheme’ was launched in 1971–1972 to cope with an increasing problem in urban areas. The programme, consisting of anti-larval measures against the vector, An. stephensi , was introduced in phases; it took nearly three decades to cover the 132 towns that had originally been identified as having populations of > 40 000 and an annual parasite incidence > 2 per 1000. The urban situation continued to deteriorate and at present contributes 8–10% of the national malaria burden. Other initiatives were a ‘modified plan of operation’, launched in 1977 in an effort to maintain the gains of the eradication days and eliminate mortality due to malaria, and the P. falciparum containment programme, which was stopped in 1988. In India, indoor residual spraying programmes have so far not been accompanied by systematic efforts to reduce the receptivity of the environment. Hence, new mosquitoes continue to emerge, filling year after year the niches vacated by adulticiding, compromising vector control operations. At the same time, residual parasite populations after relapses and recrudescences multiply in the presence of vectors (susceptible and resistant) and are disseminated in receptive and vulnerable environments. The result is persistent perennial malaria transmission » Global malaria control and elimination : report of a technical review, 2008 [↩]

- « Notable among those efforts was the near eradication of malaria in India, where the annual number of malaria cases was reduced from an estimated 75 million to about 100,000 in the early 1960s. These reductions were not sustained after the eradication period because limited resources were devoted to malaria control » http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1724/ « India launched its national malaria eradication programme in 1958, with 276 million people to be covered in the ‘attack phase’ of indoor residual spraying with DDT, the number being expanded to 424 million people in 1961–1962. In the first few years, the impact of DDT was spectacular, as the number of cases was reduced dramatically, from 110 million in 1955 to less than 1 million in 1968, and deaths due to malaria were almost completely eliminated. Resistance of An. culicifacies to insecticides began to compromise indoor residual spraying, although operations against the other malaria vectors remained unaffected. In the late 1960s, social, financial, administrative and operational problems began, including communities refusing DDT spraying, shortage of supplies, financial constraints, hilly terrain and inaccessible areas, administrative problems, inadequate surveillance, shortage of experienced, trained personnel and understaffing at all levels. As a result, the initial gains could not be maintained. In 1968–1969, the approach reverted from consolidation and maintenance to a renewed attack phase for a population of 91 million, leading to an unexpected 50% increase in the demand for DDT spraying that year. In some areas in the east of the country, the eradication programme did not achieve real success in the first place, and these areas were covered by a persistent attack phase that lasted 13–17 years. By the early 1970s, the malaria incidence (measured as the annual parasite incidence) was seen to be multiplying exponentially nationwide. » http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43903/1/9789241596756_eng.pdf [↩]

- « In 1977, malaria eradication was superseded by the Modified Plan of Operation (MPO) with a more focused attack in areas where the API was two or more. Under the MPO, which witnessed a declining trend in malaria, DDT (indoor residual spraying) was the principal insecticide. In areas with DDT resistance, HCH was sprayed and in double-resistant (DDT and HCH) areas, Malathion was used. » (DDT: The fallen angel, p. 2) [↩]

- « The impact of the vector resistance problem was felt only very gradually in the course of the campaign. During 1955-62, the number of anopheline species with physiological resistance to DDT or dieldrin (the commonly used insecticides in malaria programmes) had increased from 4 to 32. By the end of 1969, this number had grown to 38, and by 1975 to 42. The population living in areas where vector resistance created a serious obstacle to eradication (and control) counted then 256 million in four WHO regions, 29% of the total population in malarious areas in these regions. » (p.8) « The emergence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance to drugs, first documented in the 1950s–1960s in Asia and the Americas and in the 1970s in Africa, is considered one of the major impediments to successful control » The Intolerable Burden of Malaria: A New Look at the Numbers [↩]

- « Resistance to DDT was widespread in the early 1970s because of its intensive use in public health and agriculture and emerged after about 11 years of application. Although DDT has been used in limited quantities for disease vector control during the past 3 decades, there have been recent reports of resistance in malaria vectors from African countries » http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1724/ [↩]

- « In the northern part of the country, spraying with DDT started in 1959. However, this program did not significantly reduce anopheline densities or malaria transmission intensity and plasmodic index while the emergence and spread of DDT resistance was reported. This led to the stoppage of the programme in 1961. » https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5635606/ [↩]

- « Factors that could have limited the performance of these programmes include financial constraints, change in the biting and resting behaviours of the main vector species, poor implementation, emergence and expansion of dieldrin and DDT resistance in mosquito populations, the limited residual effect of DDT and dieldrin sprayings requiring frequent retreatments [33, 36–38]. The short residual effect of DDT on house construction materials inducing little direct killing of mosquitoes was also reported as a major limitation of DDT spraying programmes in West Africa » https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5635606/ [↩]

- « The three main vectors, Anopheles arabiensis [résistant au DDT en Ethiopie, Mauritius, Arabie Saoudite, Sénégal, Soudan, Swaziland, Zanzibar], A. gambiae [DDT : Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Central Afric Republic, Congo, Ghana, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Afrique du Sud, Togo, Zanzibar, Zaire] and A. funestus [DDT : Soudan], have developed widespread resistance to dieldrin and HCH, while the A. gambiae complex has developed more focal resistance to DDT. » (p.24) [↩]

- « It has been clearly documented that pesticides that are degraded slowly are more likely to produce resistance than those which degrade rapidly. Where infestation is transitory, therefore, the use of persistent pesticides is undesirable. » (Vector resistance to pesticides, p.42) [↩]

- « West and Central Africa have long been reporting high frequencies of resistance, particularly Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. These countries have widespread resistance to pyrethroids and DDT; Côte d’Ivoire has also reported resistance to carbamates and organophosphates. Ethiopia has reported resistance to all four classes of insecticide, including widespread resistance to DDT and an increasing frequency of resistance to pyrethroids. Other places in East Africa with widespread pyrethroid and DDT resistance are Uganda and its borders with Kenya and the United Republic of Tanzania. The situation in southern Africa is ocontinuing concern. Mozambique and South Africa have reported a broad spectrum of resistance over the past decade, including metabolic resistance which provided the clearest evidence leading to control failure in KwaZulu Natal in 2000 » (p.32) [↩]

- « A study by Manokore et al. [49] documented that in the Gokwe region of Zimbabwe, there is an absence of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes to deltamethrin, alpha-cypermethrin, lambda-cyhalothrin and DDT. But after this study was conducted, insecticide resistance in An. arabiensis mosquitoes has been slowly spreading and increasing in intensity [54]. Munhenga et al. [37] further confirmed the presence of insecticide resistance to permethrin and DDT in An. arabiensis mosquitoes in Gokwe. Three papers reported insecticide resistance in An. funestus mosquitoes against organophosphates, pyrethroids and carbamates [5, 52, 55]. The two recent nationwide surveys contradict each other: The one conducted by the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) [5] reports insecticide resistance in An. funestus mosquitoes, while the other one by Lukwa et al. [56] disputes this as well as previous findings. » Soko et al, 2015 [↩]

- « In 1955, it was reported in the An. gambiae species in Nigeria [24]. Thereafter, resistance has been reported in more than 500 insects, 50 of which transmit malaria parasites in humans [21, 25].» [↩]

- « In 1996, a national decision was made to change from DDT to pyrethroids for IRS. By 2000, however, the number of reported malaria cases had multiplied by approximately four. An. funestus, a vector that had been eliminated by DDT spraying in the 1950s, reappeared, and bioassays showed that the species was susceptible to DDT but resistant to pyrethroids and furthermore had a sporozoite rate of 5.4% (25), which is remarkably high by South-African standards. » [↩]

- « Despite the spread and increasing intensity of drug resistance and the progressive change of first-line drugs from chloroquine to pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine in many areas of the world, there are scant data showing that morbidity and mortality have increased during this time or that they are due to increasing parasite resistance to drugs. Trape demonstrates a two- to three-fold increase in hospital admissions and deaths, and a six-fold increase in pediatric malaria mortality from data collected prospectively when chloroquine resistance emerged in Senegal in the late 1980s and early 1990s […] Western Africa, including Senegal, has had relatively low-level resistance compared to elsewhere in Africa, so questions remain as to the percent of the increasing morbidity and mortality actually due to malaria » The Intolerable Burden of Malaria: A New Look at the Numbers [↩]

- « An example of the effect of DDT resistance on malaria control is seen in Mexico. The contrasting results obtained by control interventions in the two main regions of malaria transmission in this country, namely the Pacific coast and the Atlantic coast of the Gulf of Mexico, could be attributed to the different susceptibility levels of the vector species, A. pseudopunctipennis and A. alibmanus, in these two regions. Both species are resistant to DDT all along the Pacific coast, but remain susceptible on the Atlantic coast. An analysis of the effect of insecticide spraying on malaria in the two coastal areas indicated that DDT was highly effective in those areas where the vector is susceptible to the insecticide but, on the Pacific coast, in spite of the use of increasing amounts of DDT and other insecticides, there was no reduction in malaria incidence until other control measures were applied. » (Vector resistance to pesticides, p.26) [↩]

- « In India, resistance to DDT and HCH is widespread in A. culicifacies but its resistance to malathion is focalized. Nevertheless, in spite of evidence of reduced effectiveness, DDT is still used to protect 229 million people, HCH to protect 120 million and malathion to protect about 24 million. A. stephensi is resistant to DDT, HCH and malathion, but in rural areas, where this species is an ineffcient vector, resistant has only an insignificant impact on control. In urban areas, A. stephensi is an important vector but remains susceptible to the larvicides (usually fenthion and temephos) used for control. A. annularis, a secondary vector, is resistant to DDT and HCH. » (Vector resistance to pesticides, p.28) [↩]

- « The NAMP (formerly NMEP), sprayed 42,200 metric tons DDT (50% WP) including 11,600 metric tons for kala-azar disease control) during the 9th Five-Year Plan (1997–98 to 2001–02) and envisages the use of 66,000 metric tons DDT (50% WP) (including 13,000 metric tons for kala-azar) during the 10th Five-Year Plan (2002–03 to 2006–07) […] Further observations supporting the failure of DDT in malaria transmission interruption include the following: • In Gujarat, the API was rising in all districts receiving DDT spraying (1986–91). • In Karnataka, Primary Health Centres (PHCs) recor- ded substantial increases in API following two rounds of DDT spraying (e.g. in Gudibanda PHC from 2.4 in 1989 to 178 in 1997; in Begepalli PHC from 1.9 in 1988 to 65.4 in 1990; in Javagal PHC from 1.8 in 1992 to 176 in 1995, and in DM Kurke PHC from 10.5 in 1991 to 97.9 in 1994). […] For example, a study by NMEP reported that during the period of MPO from 1977 to 1984, insecticide-spray (DDT, HCH and Malathion) could cover only 40–60% of the targetted areas. Even if coverage increased, there is no assurance that the effectiveness of DDT would be increased, because of the resistance problems described above. (DDT: the fallen angel, 2003) [↩]

- « This reliance on DDT for malaria control is misplaced, considering the substantial scientific evidence of its ineffectiveness. Even at the height of malaria-eradication efforts, DDT-spraying did not interrupt malaria transmission in 51 million people after 13 to 17 years of regular DDT spraying, which had started in 1958. » (DDT: the fallen angel, 2003) [↩]

- « However, DDT is still used extensively for both agriculture and vector control in some tropical countries. If DDT were not used, vast populations would again be condemned to the ravages of endemic and epidemic malaria. Substitution of malathion or propoxur for DDT would increase the cost of malaria control by approximately 3.4- or 8.5-fold, respectively, and these increases could not be supported by some countries without decreasing the coverage of their control programmes. » ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CRITERIA 9 — DDT and its Derivatives [↩]

- dans le cadre de la convention de Stockholm, qui interviendra quelques années après à l’exception de l’utilisation pour la lutte contre le paludisme [↩]

- « WHO Expert Committees have continued to approve the use of DDT against susceptible malaria and leishmaniasis vector populations for indoor house spraying according to WHO guidelines and specifications. The latter include avoidance of illicit agricultural use. If DDT is to be banned, affordable and effective alternative vector control methods must be available beforehand, and the necessary financial and technical assistance must be provided to the countries concerned. » [↩]

- « DDT meets most of these criteria. It is the only organochlorine insecticide still recommended for indoor residual spraying. It is highly persistent and has a long residual effect of over 6 months on most household surfaces. It is relatively cheap compared with other pyrethroid alternatives but leaves a white residue on sprayed surfaces, which has led to high refusal rates in the past. DDT has been banned for agricultural use in many countries on the grounds of environmental pollution and potential human toxicity. However, WHO still recommends its use (WHO, 2000c; 2004c, 2004d; Nájera & Zaim, 2001, 2002,) provided that: • it is used only for indoor spraying; • it is of proven effectiveness; • WHOPES product specifications are met; and • appropriate safety precautions for use and disposal are respected. » [↩]

- « In the global malaria eradication campaign, most developing countries had been heavily dependent on external financial assistance. Apart from WHO, the main sources of funds were USAID and UNICEF. These two agencies phased out almost all their contributions to malaria programmes between 1970 and 1973—an unfortunate, though not unconnected, coincidence with the revised WHO global strategy » p.7 « The financial resources available (precondition 5) would have been adequate, if most campaigns had run smoothly and, more importantly, if they had reached the final objective reasonably within the planned time schedules. It was when programmes had to be unduly prolonged that financial support (both foreign and national) began to falter » p.8 « In 1976, the AID Auditor General (now the Inspector General) reviewed U.S. bilateral assistance to combat malaria and concluded that “the program machinery to combat malaria on a global basis has largely been disassembled.” The reasons cited were (1) increasingly tight overall AID budgets, (2) assumptions that the downward trend of malaria outbreaks/epidemics would continue, and (3) new program priorities for the diminishing AID funds and manpower » (p.3) « Faced with the recognition that malaria eradication could not be conceived as a short-term programme, UNICEF and other major collaborating agencies withdrew their support to malaria programmes in favour of general health programmes. The economic crisis of the early 1970s also contributed to the accelerated contraction of funding for malaria control. Moreover, oil shortages caused considerable increases in insecticide prices that further deteriorated the financial situation of the campaigns. » Some lessons for the future from the Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955-1969). [↩]

- « The project has successfully established an organization capable of monitoring malaria, and it has demonstrated the feasi- bility of reducing the prevalence of the disease, using DDT in a limited geographic area » (p. 20) [↩]

- « The program in Haiti is hampered by an inadequate understanding of the effectiveness of various anti-malaria measures. Program officials are aware of vector resistance to DDT, but more information needs to be obtained about locations where it still can be effectively applied. » (p.32) [↩]

- « AID provided about $4 million for a 5-year project that was approved in 1975. In addition to Nepal and AID, WHO, UNDP, and Great Britain also assisted the program. The objective was to reduce the nationwide incidence of malaria. A 1979 evaluation of the program noted (1) the import of a significant number of malaria cases from India, (2) increasing case rates where malaria-control measures were integrated into the general health services, and (3) increasing vector resistance to DDT. » (p.35) [↩]

- « Evidence that adult DDT exposure is associated with breast cancer was equivocal until Cohn et al. (2007) reported DDT levels in archived serum samples collected between 1959 and 1967, peak years of DDT use, from pregnant women participating in the Child Health and Development Studies (CHDS). Considering women ≤ 14 years old in 1945 when DDT was introduced, subjects with levels in the highest tertile were five times more likely to develop breast cancer than those in the lowest tertile. Moreover, in women exposed after the age of 14, there were no associations between the risk of breast cancer and p,p’-DDT levels. Therefore, exposure to p,p’-DDT during the pre-pubertal and pubertal periods is the critical exposure events to risk the development of breast cancer later in life. » (p.6) [↩]

- « Bornman et al. (2010) determined the association of external urogenital birth defects (UGBD) in newborn boys from DDT-sprayed and non‐sprayed villages in a malarial area. Between 1995 and 2003, mothers living in villages sprayed with DDT had a 33 % greater chance of having a baby with a UGBD than mothers whose homes were not sprayed. A stay‐at‐home mother significantly increased the risk of having a baby boy with a UGBD to 41 %. Further studies are necessary to determine possible causal relationships with DDT and any possible genetic or epigenetic predispositions. » (p.7) [↩]

- « Eskenazi et al. (2006) was the first study to show that prenatal exposure to DDT, and not only to DDE, was linked to neurodevelopmental delays during early childhood. Ribas-Fito et al. (2006) assessed neurocognitive development relative to DDT levels in cord serum of 475 children. At age 4, the level of DDT at birth was inversely associated with verbal, memory, quantitative and perceptual performance skills, and the associations were stronger among girls. Torres-Sanchez et al. (2007) found that the critical window of exposure to DDE in utero may be the first trimester of the pregnancy, and that psychomotor development in particular is targeted by the compound. The authors also suggested that residues of DDT metabolites may present a risk of developmental delay for years after termination of DDT use. Sagiv et al. (2008) demonstrated an association between low-level DDE exposures and poor attention in early infancy. In a follow-up study, they found that prenatal organochlorine DDE was associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) behaviour in childhood (Sagiv et al., 2010). » (p.8) [↩]

- « Les plus fortes augmentations significatives de risque ont été observées dans la méta-analyse portant sur les agriculteurs ayant travaillé au moins 10 ans dans une ferme ainsi que pour ceux qui ont été exposés au DDT. » (p.46) [↩]

- « évaluer la vitesse d’acquisition visuelle et la motricité fine. Enfin, il existe de fortes présomptions selon lesquelles l’exposition in utero au p,p’-DDE ou HCB (les 2 composés étudiés principalement), aurait un impact sur la croissance et le développement de l’obésité chez l’enfant. » (p.77) [↩]

- « Les études transversales réalisées parmi des populations exposées professionnellement au DDT ou résidantes dans des zones où l’usage de ce dernier fut important (Mexique, Afrique du Sud) tendent à montrer des associations entre l’exposition et la dégradation de divers paramètres spermatiques. En revanche, les études menées en population générale aboutissent à des résultats contradictoires. Seules celles réalisées parmi les populations Inuits, forts consommateurs de denrées animales contaminées (situés au sommet de la chaîne trophique) par le DDE, montrent assez fréquemment des associations avec des atteintes spermatiques et un délai nécessaire à concevoir allongé. En Californie, une étude transversale réalisée parmi des agricultrices n’a pas montré d’association entre le délai nécessaire à concevoir et la concentration circulante en DDE ou en DDT. Une étude chinoise réalisée parmi des femmes récemment mariées, travaillant dans l’industrie textile et sans enfant, a montré une association significative entre des concentrations croissantes circulantes en DDT et le risque d’avoir un cycle menstruel court (<21 jours). » (p.86) [↩]

- « En effet, certains composés exercent aussi des effets spécifiques sur des voies de signalisation qui pourrait être à l’origine des perturbations : • de l’immunité via des modifications de la production de cyto- kines (dieldrine, DDT, toxaphène, triazine,) ou via un effet cytotoxique direct sur les cellules immunitaires (DDT, lindane, pyréthrinoïde, alachlore, triazine) » (p. 104) [↩]

Bravo pour ce remarquable travail!

Quand je pense à la façon dont l’AFIS traite la question, reprenant sans nuance les propos de dives lobbys, cela me rend malade.

Au fait vous avez essayé de dialoguer avec eux?

J’ai tweeté l’information à l’auteur du blog Sham and Science, qui fait partie du comité de rédaction de l’AFIS. Il l’a retweeté. Mais je ne les ai pas contactés officiellement pour leur proposer la publication de cet article.

Cela étant je suis un peu échaudé par une proposition d’article faite en octobre 2013 au sujet de l’énergie en réponse à un article de l’AFIS sur le sujet qui ne rentrait absolument pas dans le fond du problème, dans les ordres de grandeur en jeu et qui se contentait (en gros) d’affirmer que l’innovation technologique serait la solution au problème énergétique. Cet article de trois pages, malgré plusieurs relances, serait toujours en relecture depuis 6 mois. C’est une des raisons pour laquelle je n’ai pas proposé l’article à l’AFIS, l’autre raison c’est que l’auteur de l’article sur le DDT est aussi le rédacteur en chef de la revue ce qui me semblait rendre la chose plus complexe…

Bonjour,

Je suis au comité de rédaction de l’AFIS. Je n’ai pas vu votre article de 2013, mais il arrive que des papiers trainent très longtemps sans mauvaise volonté de notre part. Nous ne sommes qu’une poignée de bénévoles, occupés par ailleurs. La lenteur ne veut pas forcément dire que nous nous voulons pas de votre article. Je jetterai un œil.

Quant au DDT, je ne suis pas compétent sur cette question personnellement, mais différents échos que nous avons eu nous on fait entamer un brainstorming… c’est un début.

Bonjour,

Merci beaucoup pour la réponse rapide !

Pour le DDT je ne suis pas spécialiste non plus, mais j’ai regardé les informations disponibles sur le sujet, en me concentrant autant que possible sur des sources provenant de l’OMS (en l’occurrence 17) pour éviter la tentation du cherry-picking qui consisterait (par exemple) à utiliser comme source un article de J. Gordon Edwards, publié en 2004. Cet article a été publié dans Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons, journal qui semble critiqué pour certaines publications… inattendues (sur le SIDA, le réchauffement climatique…). Cet article, toujours, n’est en fait qu’une réécriture d’un article publié en 1999 avec Steven Milloy sur junkscience.org. Milloy : il serait trop long de faire toute sa bio, mais sa spécialisation est de vendre du doute (sur le réchauffement climatique, le tabagisme passif, l’ozone, l’évolution…).

Pourquoi parler de cela ? Parce que cette publication « scientifique » est citée par l’article de l’AFIS pour tenter de montre que certaines organisations internationales ont fait pression pour bannir le DDT. En l’occurrence, ce que dit l’article de l’AFIS s’appuyant sur Edwards, c’est que la Banque Mondiale aurait conditionné une aide à l’Inde à un arrêt de l’utilisation du DDT. J’ignore si c’est vrai. Peut-être, mais Edwards ne cite pas ses sources ce qui empêche de vérifier l’information. Par ailleurs tout dépend de ce qu’on appelle « utilisation du DDT ». S’il s’agit d’arrêter l’utilisation du DDT en agriculture c’est plutôt raisonnable, puisque l’épandage massif contribue largement au développement de résistance, rendant alors la lutte contre le paludisme plus complexe.

Il est très bien également qu’un brainstorming ait lieu dans l’association au sujet du DDT. Je me permet de suggérer de l’organiser avant la publication d’un tel article la prochaine fois 😉

Excellent billet.

Une toute petite remarque, sur la forme :

« Elle mentionne aussi la dégradation de paramètres spermatiques ou un délai nécessaire pour concevoir allongé, chez les personnes les plus touchées par le DDT » : eh bien, ma foi, elles n’ont qu’ à baiser debout et le problème sera résolu…

(à moins bien sûr que vous n’ayez voulu dire « un allongement du délai nécessaire pour concevoir »)

On fait tout un foin avec le DDT, mais finalement les solutions sont simples 😉

(merci c’est corrigé)

Travail copieux, il va me falloir du temps pour en faire le tour !

J’ai par contre été interpellé par la discussion sur le décompte des morts du paludisme. Au delà des chiffres eux même, qui dépendent de la précision et de l’effort du dépistage, on est sur un problème assez costaud. 1) Le nombre de cas déclarés par exemple au Gabon est ridicule. 2) Le paludisme a un fort impact sur la fréquence de l’allèle de l’hémoglobine responsable de la drépanocytose. Et la drépanocytose est une cause importante de mortalité infantile dans de nombreux pays d’Afrique (au moins centrale).

« C’est une maladie qui tue beaucoup mais pas tant que ça. » Au delà des poils qui se hérissent et du relativisme vidant la phrase de son sens (une comparaison serait bienvenue), il est fort probable que cette proposition soit fausse.

Mes excuses pour le ton en décalage avec la quantité de travail fournie dans cet article… mais il y a peu de maladie qui ne tuent pas « tant que ca » d’un point de vue humaniste, du coup ca me gratte.

Merci pour le commentaire.

Effectivement la formulation « mais pas tant que ça » n’est pas très heureuse. Je vais reformuler. Le « pas tant que ça » fait référence aux nombres mis en avant par certains (2 ou 3 millions de morts). Le paludisme ne tue pas autant que le prétendent certains, d’après les chiffres officiels. Après il est clair qu’avoir une estimation fiable est complexe (c’est aussi pour ça que l’OMS fournit des intervalles et non une valeur précise). Peut-être le nombre est-il sous-estimé mais dans ce cas les personnes avançant des nombres plus élevés devraient être en mesure de le justifier avec des sources solides, ce que je n’ai pas vu.

Je suis en train de me dire que le nombre de morts liés au paludisme est une question intéressante indépendamment des insecticides. Je vais regarder de ce pas si je trouve de la littérature.

En fait cette question n’a que peu d’impact sur le déroulement de ton propos. Ca donne le sentiment (tout à fait compréhensible) que les thèses défendues t’énervent tellement que tu veux absolument en saper le moindre élément.

Ça a pu jouer c’est sûr 🙂

Mais je préfère me dire que je voulais illustrer par là le manque de sérieux des personnes qui relaient ces thèses qui ne prennent pas la peine de vérifier leur information (alors qu’elle se trouve assez facilement sur le site de l’OMS) et qui relaient une information qui était juste au mieux dans les années 90. Il se trouve aussi que cela peut être un marqueur de l’origine de leur thèse : elle s’est développée dans les années 90 (comme je l’explique ici).

Concernant les décès, et indépendamment des insecticides, la faim (et donc la pauvreté) est un facteur aggravant du paludisme : http://www.worldhunger.org/articles/Learn/world%20hunger%20facts%202002.htm#Children_and_hunger